By Marieke Dhont

Post-doctoral researcher@EVWRIT

The Septuagint, the Greek translation of the Jewish scriptures born out of the encounter of the ancient Mediterranean East with the Hellenistic expansion of the Greek world, represents the oldest substantial corpus of translated texts at our disposal. The corpus was produced book per book by translators unknown to us, sometime between the late third century BCE and the first century CE, in Egypt and/or Palestine, and became the Bible for Greek-speaking Jews and early Christians.

The Early Days of Septuagint Research: The Septuagint as a Textual Witness

In the last thirty or so years, scholarship has increasingly approached the Septuagint as the literary and socio-cultural artefact of a community of Hellenophone Jews. Until the late twentieth century, however, the main focus of Septuagint research was its use as a textual witness to a Hebrew source text that is now lost to us.

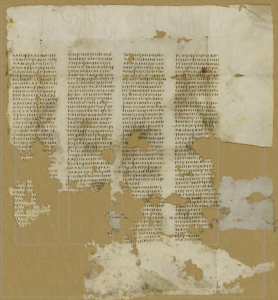

Image from the Codex Sinaiticus, dated to the fourth century CE, containing Deut 3:8-4:1, available via https://codexsinaiticus.org

The Septuagint, the oldest complete manuscripts for which date back to the third and fourth century CE, was mined for textual variants in relation to the significantly younger, medieval Masoretic Text, the oldest text of the Hebrew Bible at our disposal until the discovery of the fragmentary Dead Sea Scrolls. For each variant, it was then established whether the cause for the variant would lie with the translator, either as the result of a presumed mistake or of their translation methods, or if the variant reading in question reflected an underlying Hebrew text that differs from the Masoretic Text.

For example, in Exod 1:5, the Masoretic Text states that the number of Jacob’s descendants travelling to Egypt was seventy, while the Septuagint mentions there were seventy-five.

For long, the Septuagint was often thought to be inferior to the Masoretic Text. The discovery of the Dead Sea Scrolls (dated approximately to the third century BCE to the first century CE), however, showed us that at times the Septuagint would indeed agree with the Scrolls against the Masoretic Text.

When the Scrolls were found, it became clear that the translator of Exodus probably had a Hebrew source text reflecting that same reading of seventy-five: a fragment referred to as 4QExoda, which contains Exod 1:3-17, also mentions the number “five” here.

The Septuagint and Textual Plurality

The Dead Sea Scrolls also showed us that in the Hellenistic period different versions of the same scriptural book circulated alongside one another – a phenomenon often referred to as “textual plurality”. Prior to the establishment of the Masoretic text, the textual world of ancient Judaism and its scriptural traditions was rich and varied – and the Septuagint is part of that richness, of the textual plurality of ancient Judaism.

The Septuagint as a Cultural Product of Hellenistic Judaism

The Septuagint is the first attested step in a centuries-long tradition of scriptural translation, but how do we understand the Septuagint as a cultural product, meaning as Greek text within a Jewish context and as a textual product within the Greek-speaking world? In this respect, the language of the Septuagint has been an important area of research.

For example, on the translators’ part, adherence to the form of the Hebrew would sometimes override the desire to use of Greek idiom. By way of illustration, we may look at the expression of greetings. In Hebrew, the idiom “to greet someone” consists of a verb שׁאל, ša’al, “to ask” and the noun שׁלום, šalom, “peace” introduced by a prepositional lamed. The person who is greeted is introduced also by a prepositional lamed. Taking the expression piece by piece in English, we get something like “to inquire for someone’s peace.” The Septuagint rendering of this idiom varies. In 1Sam 10:4, we find καὶ ἐρωτήσουσίν σε τὰ εἰς εἰρήνην “and they will ask you about matters regarding peace.” The translator has rendered the elements of the Hebrew idiom individually into Greek with word-by-word equivalents. The result is a Greek construction that reflects the Hebrew source text in a way that is not idiomatic in Greek. In such a case, scholarship speaks of interference. Alternatively, when a translator aims to express the meaning of the Hebrew in Greek idiom, we encounter renderings such as ἠρώτησεν δὲ αὐτούς Πῶς ἔχετε; “they asked them, ‘How do you do?’” in Gen 43:27 or καὶ ἠσπάσαντο αὐτόν “and they greeted him” in Judg 18:15. The meaning of the Hebrew and the Greek essentially remains the same, but the translators of the various books display different attitudes as to what they considered the most appropriate rendering in Greek.

Interference versus Idiom

The degree of Hebrew interference versus Greek idiom, however, is a long-standing topic of debate in Septuagint scholarship. The language of the Septuagint is, admittedly, different from that of Greek literary works – but how do we understand this difference? Scholars who emphasized the extent of interference from the Hebrew in the Septuagint understood the Greek as stylistically poor or odd and often posited that Hellenophone Jews either used a specific Judeo-Greek dialect or were poorly educated in Greek. However, in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries, the field of Classics has seen an increase in interest in the Hellenistic period and its written output, including inscriptions as well as sub-literary and documentary papyri. The increase in available papyri and inscriptions, as well as the increasing access to and searchability of this material through databases, has given a significant boost to Septuagint scholarship and has highly increased our understanding of the language of the Septuagint.

For example, the Greek Psalter contains many different epithets for God. The translator sometimes deviates from the Hebrew text. In Ps (LXX) 90:2, for example, we read ἀντιλήμπτωρ μου εἶ καὶ καταφυγή μου, “You are my defender and my refuge”, where the Hebrew reads “my refuge and my fortress.” While ἀντιλήμπτωρ was long considered a specifically “biblical” word, Hellenistic papyri show that the term was used for the Ptolemaic king or other officials in the context of requests, often to resolve legal disputes. See, for example, lines 19-20 in BGU IV 1139 = TM 18583 (first century BCE, https://papyri.info/¬ddbdp/bgu;4;1139):

ἀξιῶ σε̣ τὸν πάντ(ων) σωτῆ(ρα) καὶ ἀντιλ(ήμπτορα) ἐά[ν σ]οι φαίνη(ται) σ̣υ̣ν̣τάξαι…

Therefore we ask that you, the saviour and defender of all, if it seems good, order…

The occurrence of the same word in the Septuagint and contemporary papyri explains not only the translator’s choice of words, but also why the translator deviates from the Hebrew: they use terms specific of the cultural context that would resonate with their audience.

The papyri have shown that the language of the Septuagint essentially reflects post-classical Greek. By extension, contextualizing the language of the Septuagint helps us to contextualize ancient Jews as insiders within the Greek-speaking world, rather than as outsiders. The question of language now is one, not of the translators’ ability in Greek, which has been carefully established, but of register and variation in post-classical Greek.

EVWRIT and the Septuagint

As we move away from understanding the Septuagint primarily in relation to the Hebrew, we can move towards understanding the Septuagint within the history of Greek. Research into the language of the Septuagint thus far has primarily focused on analyzing the vocabulary of the Septuagint; less attention has been paid to the syntax of the Septuagint in relation to papyri. It is in this regard in particular that the EVWRIT project and its database will offer a wealth of new material for those studying the Septuagint. The EVWRIT database provides a tool for and opens up new avenues to studying the syntax of the Septuagint and the questions of interference and contact-induced linguistic change.