by Leonardo De Santis

Visiting PhD fellow

Telling a joke is an action that many Italian people perform every day. However, very few Italian people realise that, when they are telling humorous stories that are set in the past, they use almost exclusively the historical present (i.e. a present tense that refers to the past: “He goes” instead of “he went”). Telling jokes is not a thing that is learnt in schools and no one teaches people that, when they are telling a joke, they have to use the historical present. However, almost every person in Italy uses the historical present when they are telling a humorous story.

A similar phenomenon occurred also in Post-Classical (especially Late-Antique and Early Byzantine) Greek in the case of the so-called “narrative imperfect”, i.e. an imperfect form that is used instead of an aorist form.

Greek is a language in which verbal aspect plays a major role. Aspects are generally defined as ‘different ways of viewing the internal temporal constituency of a situation’ (Comrie 1976: 3).

Imperfective aspect describes an event in terms of temporal unboundedness, without any reference to its transition phases (e.g. Allan 2017: 118). A typical imperfective form is the English past progressive. If I say: “John was walking”, I am just saying that, at a precise moment in the past, John was walking, without giving any information about the moment in which John began to walk or the moment in which John stopped. The event is depicted as “in progress”.

Perfective aspect describes an event in terms of temporal boundedness, with reference to its transition phases (e.g. Allan 2017: 118). This type of aspect describes an event as a complete whole. If I say: “Yesterday John walked for two hours”, I am saying that yesterday John began to walk, walked for two hours and then completed the action of walking. The event is depicted as a “complete whole”.

In Ancient (and Modern) Greek, the present stem conveys imperfective aspect and the aorist stem conveys perfective aspect. Imperfect and aorist indicative are, respectively, an imperfective and a perfective past.

In Ancient Greek, but also in many other languages, perfective past forms usually ‘push forward’ the narration of the main sequence of the events in a story by adding new information. On the contrary, imperfective past forms are used to describe all the actions that don’t push forward the sequence of the events. They have a background function and are used in descriptions, comments made by the narrator exc. (Bentein 2016: 26).

However, in Ancient Greek, imperfective past forms can be used in perfective contexts to push forward the narration. Such an imperfect form is called “narrative imperfect”. A good example of a narrative imperfect is found in the following passage from the fourth-century Historia Lausiaca.

(1) H. Laus. 16.2 (ed. ed. Mohrmann, Bartelink, Barchiesi 2001)

Πρὸς ὃν ἀπεκρίνατο ὁ μακάριος Ναθαναὴλ καὶ ἔλεγε …

‘The blessed Nathanael answered and said (lit. ‘was saying’) to him …’

In (1) the verb λέγω is employed in a perfective context (it is coordinated with the aorist ἀπεκρίνατο) and pushes forward the narration by telling us what Nathanael said to the demon that is bothering him, but the verb λέγω is in the imperfect indicative.

In this case, the use of the narrative imperfect draws the attention on the direct speech that follows the verb λέγω. In this example, the narrative imperfect seems to have a ‘preparatory’ function (see, for example, Allan 2017: 105, 109). It describes a new action, but at the same time it sets the stage for the new events which follow the action (in this case, the direct speech).

This ‘preparatory’ function seems to be the main function of the narrative imperfect in Ancient Greek. However, there are some examples in which the function of narrative imperfect forms is not detectable, as in this passage from Dionysius of Halicarnassus’ Roman Antiquities:

(2) H. 1.79.5 (ed. Fromentin 1998)

τίθενται τὴν σκάφην ἐπὶ τοῦ ὕδατος. ἡ δὲ μέχρι μέν τινος ἐνήχετο, ἔπειτα τοῦ ῥείθρου κατὰ μικρὸν ὑποχωροῦντος ἐκ τῶν περὶ ἔσχατα λίθου προσπταίσει περιτραπεῖσα ἐκβάλλει τὰ βρέφη.

‘They [i.e. Amulius’ servants] put the cradle on the water. It floated (lit. was swimming) for a while, but, since water was slowly retreating from the extreme places it had reached, it [the cradle] bumped into a rock. Turning upside down, it threw out the newborn babies.’

In this passage, Dionysius describes the way in which Romulus and Remus, who had been thrown in the river Tiber by Amulius, are saved. The cradle in which the newborn babies are put bumps into a rock near the shore of the river and the babies manage to reach the shore.

In (2) all the finite verb forms apart from ἐνήχετο are historical presents. The verb ἐνήχετο describes a new action that involves the cradle: after being put on the water, the cradle floats for a while. The verb form ἐνήχετο is a narrative imperfect, but in this case the function of the narrative imperfect is not detectable. The imperfect ἐνήχετο does not draw the attention on what follows it and does not have a preparatory function: it simply says that the cradle floated for a while.

The use of narrative imperfect is a very little studied phenomenon in Ancient Greek, especially for Late-Antique and Byzantine Greek. For this stage of the Greek language, the only studies available are the studies by Moser (e.g. Moser 2017).

In Classical and Post-Classical Greek, narrative imperfects are used frequently and with a wide range of verbs.

On the contrary, in Late Antiquity, the use of narrative imperfect forms depended mainly on the register and on the genre of the texts. Register is ‘the fact that the language we speak or write varies according to the type of situation’ (Halliday 1978: 31-32).

The linguistic features that a text exhibits vary according to the situation for which the text has been produced. For example, an oral text will be linguistically different from a written text; a medicine book and a book about historical linguistics will employ a different lexicon; a private letter and a formal petition will employ different lexicon and different grammatical constructions.

In Ancient Greek, we have always to deal with written texts, and the field of the texts (e.g. medicine, historiography exc.) mainly influences the lexicon, but not the grammar. On the contrary, the social relation between the interactants seems to influence also grammatical choices.

For example, Agathias’ Histories, a sixth-century highly classicizing text which aimed to be read by the highly educated élite of the empire, exhibits grammatical choices (e.g., extensive use of the dual number) that are very different from the choices made by the author of the Historia monachorum in Aegypto. This latter text is a text about the monastic life in Egypt written by an anonymous monk in a (mostly) plain and simple Greek. It is meant to be read by a larger number of people and not (only) by the élite. As a consequence, the Greek of the Historia monachorum shows many Post-Classical features (e.g., the absence of dual number). In this way, the text was felt by its readers as ‘nearer’ to their everyday language, and it was easier for it to reach a larger audience.

In the case of narrative imperfect forms, the higher the register is, the more widespread narrative imperfects are.

In lower-register narrative texts, such as hagiography, the use of narrative imperfect forms is rarer and is restricted to the verba dicendi (i.e. verbs related to the act of speaking, e.g. “to say”, “to ask”, “to answer”, “to teach”…). In high-register historiographical texts, such as Agathias’ Histories, narrative imperfect forms are more widespread and are not restricted to verbs of saying.

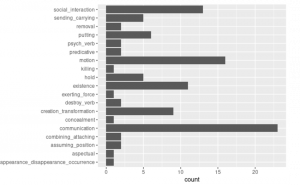

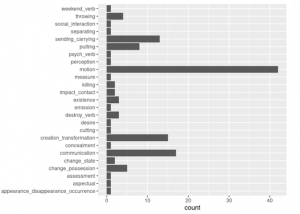

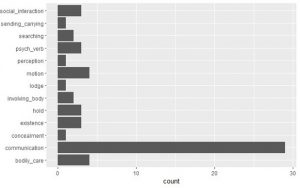

The following graphs show the absolute frequency of narrative imperfect forms (on the horizontal axis) and the verb classes which are used in the narrative imperfect (on the vertical axis) in some Classical, Late-Antique, and Early Byzantine prose texts. As for the verb classes, the classification by Levin 1993 has been used.

The texts that have been chosen are Thucydides’ Histories, Agathias’ Histories and Palladius’ Historia Lausiaca.

Thucydides writes his historiographical work in high-register Attic Greek. Sometimes, he uses rare and poetical words and his Greek is full of long, intricate sentences with many subordinate clauses.

The Historia Lausiaca is a late-antique hagiographical work. It aims to reach a large audience and, as a consequence, it employs a rather simpler Greek. It shows many non-classical features both in the lexicon and in the grammar (such as the use of ἵνα followed by the indicative).

Agathias’ Histories are an early Byzantine high-register text. Agathias’ models are the Classical historiograpical works by Herodotus and Thucydides. He uses rare and poetical words and writes in a classicizing Greek full of rare grammatical features, such as the pluperfect or the future optative. This latter grammatical feature was already rare in the Classical age and was no longer used in the spoken language.

Thucydides’ Histories, book 1, Classical Greek:

Agathias’ Histories, books 1-2, Early Byzantine high-register Greek:

Palladius’ Historia Lausiaca, middle-low-register Early Byzantine Greek:

As the images show, the Early Byzantine high-register Histories of Agathias display a more classical behaviour, especially with verbs of motion, saying and creation. In this text, narrative imperfect forms are more widespread and are used with a wider range of verb classes, in a way that is similar to the classical Thucydides. On the contrary, in the Late-Antique lower-register Historia Lausiaca, the narrative imperfect is commonly employed only with verba dicendi.

It is possible that the extensive use of narrative imperfect forms in classical and Early Post-Classical historiography was felt as a characteristic of the historiographical genre and that it was imitated by late-antique and early Byzantine historians, who wrote in high-register atticizing Greek. It was probably not a (completely) conscious phenomenon, since no one taught people that, when history is the main topic of a literary work, narrative imperfects must be used.

It is possible that the situation was similar to what happens with jokes in Italian. No one explicitly teaches that, when a joke is told, historical present must be used. However, when someone is telling a joke, historical present will probably be the main narrative tense. It is an implicit convention. In a similar way, no one explicitly taught late-antique historians that they had to use narrative imperfects in their historiographical works, and yet high-register historiography is full of narrative imperfects, probably according to an implicit convention.

Bibliography

Allan, R.J. 2017. The Imperfect Unbound: A Cognitive Linguistic Approach to Greek Aspect, in Bentein, K.; Janse, M.; and Soltic, J. (eds.), Variation and Change in Ancient Greek Tense, Aspect and Modality (Leiden; Boston, 2017), 23: 100-130.

Bentein, K. 2016. «Aspectual Choice and the Presentation of Narrative. An Application to Herodotus’ “Histories”», Glotta 92 (1): 24-55.

Comrie, B. 1976. Aspect. An Introduction to the Study of Verbal Aspect and Related Problems. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Fromentin, V. 1998. Denys d’Halicarnasse: Antiquités Romaines, vol. 1. Paris: Les Belles Lettres.

Halliday, M.A.K. 1978. Language as Social Semiotic: The Social Interpretation of Language and Meaning. London: Edward Arnold.

Levin, B. 1993. English Verb Classes and Alternations: A Preliminary Investigation. Chicago and London: The University of Chicago Press.

Mohrmann, C.; Bartelink, G.J.M.; Barchiesi, M. 2001. Palladio. La Storia Lausiaca, 6th ed. Milano: Fondazione Lorenzo Valla.

Moser, A. 2017. Aktionsart, Aspect and Category Change in the History of Greek, in Bentein, K.; Janse, M.; Soltic, J. (eds.), Variation and Change in Ancient Greek Tense, Aspect and Modality (Leiden; Boston: Brill, 2017): 131-157.