By Kyriaki Giannikou

Research assistant@EVWRIT

Among all types of documentary texts written and preserved on papyrus, accounts have undoubtedly received the least attention, perceived as “unremarkable” economic texts (Jones in Bagnall (ed.) 2009, 370). Although taken into account when in need of compiling economic data (eg. wages, prices of goods etc.) to facilitate, among others, the approximate placement in time of undated papyri (eg. Johnson and West 1949), the analysis of those “mere lists of income and expenses” (Jones in Bagnall (ed.) 2009, 370) often ends there.

Undoubtedly, the absence of a high degree of standardization in terms of both form and content combined with the hyper-concise and usually fragmentary nature of the preserved text deter scholarship from a comprehensive study on accounts. However, hereby, I will attempt to highlight some characteristics of accounts and, more specifically, entries concerning builders and building practices. I intend to do so by presenting a modern account of this type and its characteristics, tracing them back to either similar or conflicting characteristics of ancient, parallel documents. What this modern source could bring to the discussion is debatable but possibly useful, as I was able to collect different testimonies of the contractor’s family environment, which provided an extra layer of meaning and posed questions to the ancient sources.

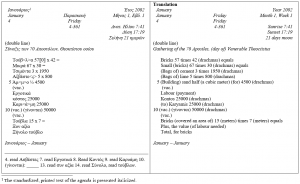

Our modern source of the recent past dates back to 2002 and originates from a village in Chios, Greece. It’s part of a standard, lined-paper agenda used by Ioannis M. Kontos, an expert builder and contractor, to keep track of his work-related finances. For the purpose of this post, I adduce the following two entries:

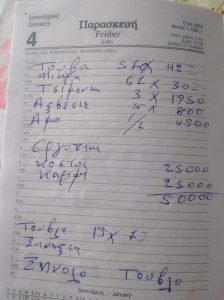

- Entry of January 4th

- Entry of June 23rd (translation on the right)

First glance: handwriting and layout

| Building Account: cost of materials, wages, final cost (Nea Potamia, Chios, Greece, January 4th 2002) | |

|

Beginning with our modern source, the handwriting is definitely not immaculate, but it remains legible. It is not cursive and ligatures are almost entirely absent. Overall, it constitutes a quite slow hand, the flow of which seems difficult to maintain.

With regards to the page layout, neither the line division itself is respected (eg. l.4 αξβέστε<ς>: written over the line) nor the writing is always parallel to the lining (eg. l.2 μικρά: flowing between two lines). This is also the case for the hourly division; it is not taken into consideration, as there is no need of such details. However, the entries were written or at least refer to the date indicated on the top of the page, proven by notes of the same agenda on preparations for the village’s annual festivity. |

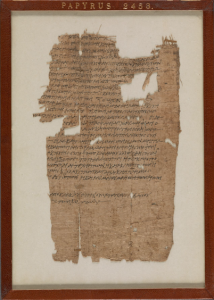

| P.Ryl. IV 642 = TM 32768, verso (Fr1) (Building Account, Hermopolis, early 4th CE) | |

|

Similarly, this ancient specimen of the same document type is far from polished in terms of appearance. Although the handwriting seems to reveal a person who writes regularly and probably professionally, it is the speed of writing which increases the amount of ligatures and reduces legibility; in extreme cases (eg. l.12 Ἀμμωνίου) words are written as ribbon-like lines and individual letters are hardly distinguishable.

Concerning the layout, the account is chronologically organized by the specification of the date each entry corresponds to, at the beginning of a line (eg. l.8 ιδ, l.9 ις etc.). All entries probably refer to the month of Mesorē, stated once on the recto (l.8) of the document. Appearance-wise, it’s messy; the interlinear space is by no means consistent (eg. ll. 13-15-15 compared to 10-11) and the lines of writing are not always parallel to each other. Both fast-penned, highly cursive and slow, awkward handwriting, along with a clumsy handling of the page layout, reveal the same thing; in both cases, practicality is prioritized over neat appearance, and that’s highly expected when dealing with private (building or not) accounts. These notes were intended for personal use (in the case of the modern parallel) or at least use by a very specific set of people, for example a steward who penned it and the builder who is familiar with the content and can easily access it through messy notes. In the case of the modern text though, there is an extra layer, competence; it was a barely schooled builder who wrote the notes down, while the fluent hand of the ancient text allows the assumption of a quite well-trained hand. This focus on practicality is particularly accentuated when comparing the documents above to the following estimate of a building project. |

| P.Oxy. XII 1450 = TM 21851 (Estimate of Repairing a Public Building, Oxyrhynchos, 249-250)

(translation: https://archive.org/details/oxyrhynchuspapyr12gren/page/144/mode/2up) |

|

|

In this case, estimates on the cost of repairing a public building are submitted to the local authority, probably for approval. Although the content is close to what we would expect from a building account, here it takes the form of an official document.

This is clearly pictured in the way the document was written; the handwriting is neat, formal and, thus, highly legible. The individual letters are fast but still carefully penned and frequently ligatured. In terms of layout, the text is beautifully penned on the page; the interlinear space remains consistent, while the lines form a block of text, retaining a clear margin on the right side. The date the document was drawn up is also written at the bottom part of the page, clearly separated from the main body of the text. All three documents deal with the cost of building and wages, but the function, and thus the appearance, of the third one is different; the focus shifts from practicality to formality and the reader to whom it’s addressed shifts from a building expert to a local authority. |

Content: note-taking method

The accounts’ focus on practicality and efficiency also extends to their content.

P.Ryl. IV 642 = TM 32768, verso (Fr1) (Building Account, Hermopolis, early 4th CE)

In this representative example of an ancient building account, the entries take the form of elliptical constructions. The text is concise; all important details are given and the elided elements (mostly verbs) are easily recoverable, while the text remains far from verbose. Space and time (both when writing and reading) efficiency, is also achieved by extensive use of abbreviations. Frequently used terms related to money (eg. ἀργύριον, δραχμαὶ) or the building profession (eg. οἰκοδόμος, ἐργάτης), along with common prepositions and adverbs used in accounts, are abbreviated due to being familiar, recurring and highly expected in that context, along with easily predictable endings of the names mentioned (eg. l.16 Χώλ(ου)).

The text does not present mistakes in terms of orthography, which could be due to the fact that most of the text is being abbreviated and pretty standard.

Building Account: cost of materials, wages, final cost (Nea Potamia, Chios, Greece, January 4th 2002)

In our modern parallel text, the information is written down in the form of a brief list; even more elliptical note-taking than above. The content remains pretty clear, except perhaps in ll.12-14; still, it must have been clear for its writer, fulfilling its purpose as a note.

In this case, the orthography is way more problematic. Accentuation is totally omitted, along with several letters, while others are mixed up. The confusion of σ and ξ is very frequent. In l.4 (Αξβέστε<ς>), it can be justified taking into consideration the pronunciation and the paleographic closeness of ζ and ξ. Factors like the local dialect or lack of knowledge might account for the rest.

Once again, when formality is added to the equation due to the change of the receiver of the information, the differences are evident, also in terms of content.

P.Oxy. XII 1450 = TM 21851 (Estimate of Repairing a Public Building, Oxyrhynchos, 249-250)

(translation: https://archive.org/details/oxyrhynchuspapyr12gren/page/144/mode/2up)

The aforementioned official document providing estimates for a building repair is descriptive and detailed, in contrast to the accounts. Even the abbreviations are kept to a bare minimum, retaining only those indicating the measuring unit (l.1 ἐμβαδικ(ῶν) πηχ(ῶν)) and the symbols indicating the currency (eg. l.6 (δραχμῶν), (ὀβολοῦ), (πεντώβολον)), along with (perhaps) the terms “more or less” (l.9 πλ(εῖον) ἢ ἔλατ(τον)) that are also regularly repeated unabbreviated.

In terms of orthography, we wouldn’t say it’s very problematic, but mistakes are not absent; all of them can be explained taking iotacism into consideration.

Practice beyond the documents: labour remuneration

Building Account: labour remuneration (Nea Potamia, Chios, Greece, June 23rd 2002)

The entry of June 23rd refers to calculations on the remuneration (πληρωμή) of the construction team, the contractor himself included. He worked for 5 days, his wage not given, as it was probably negotiable and changed according to the agreement and the total remuneration he received for each project. His main, “permanently” employed worker and assistant (Ξένος) also worked for 5 days. Meanwhile, during the week, different other workers and experts also worked for him, receiving one daily wage each, ranging from 30 to 60 euros.

Dealing with this modern source, I was able to access background information on the payment of workers by the contractor through testimonies, which made it possible to explain the difference in the workers’ remuneration. The main worker (Ξένος) received 30 euros as a daily wage; he was an unskilled worker who mainly assisted the contractor in a range of different tasks. The same holds true for the lastly listed and equally paid worker (Γεώ(ργιος) Λ<ι>ονής). Note that the “permanent” employment of the former is an additional feature that makes a lower daily wage expected. The rest of the workers seem to have some kind of expertise, hence their higher wage; Lampros’ (l.4) expertise could not be recalled by the contractor’s family environment, but it seems that Kyriakos (l.5) was an expert builder (daily wage of 60 euros), while Psilis’ (l.6) specialty was formwork (daily wage of 50 euros).

Taking into consideration both that this entry and notes on payment are written on a Sunday and that the payment refers to a maximum of 5 days of labour, it stands to reason to assume that the contractor used to pay his workers every end of the week. Indeed, testimonies helped to confirm that.

Lastly, I focused on the type of labour remuneration, which in this case is clearly monetary. However, testimonies revealed that offering of goods was also a common practice for the contractor, but not as a labour remuneration; as an act of appreciation and community bonding, on top and beyond any employer-employee relations.

Labour remuneration in Roman and Byzantine Egypt

Concerning workers’ wages, ancient sources vary significantly. Freu (JRA 28, 161-177) refers to “the milieux of employment, availability of the manpower, forms of employment, and social statuses of partners” as substantial criteria for differentiation in wages (p.162).

As in modern times, there was a wage difference between unskilled and skilled workers which, though, seems to have been sharper. Casual, unskilled workers received a wage two to four times lower than building experts (p.167).

Similarly, the duration of the employment could influence labour remuneration, but it is not entirely clear how (p.177). Aside from that, we observe an important difference. The duration of employment seems to have directly influenced the type of remuneration as well. More “permanent” employees normally received a small amount of cash per month (ὀψώνιον) along with food or other types of indirect payment, while casual workers mainly received their daily wage (μισθός) in cash, without any addition of food being systematically indicated (p.163).

Lastly, in contrast to our modern source, where we often find entries listing the same people receiving the same daily wage, ancient sources depict a daily wage that could possibly fluctuate day by day (p.163).

To conclude

I would like to conclude by pointing out that even such seemingly uninformative and not interesting documents like (building) accounts can give us more information on the way people engaged in efficient note-taking, organized and executed their professional responsibilities, and, comparing them to a modern source, the way they did so is not as far from our reality as we might think.

What would be even more interesting for further research is the comparison of wages and cost of basic goods, to be able to draw some indicative conclusions on how the purchasing power of a construction worker evolved through the ages or even the effect of reformations on those (eg. the Edict of Diocletian or the Reform of Constantine compared to the transition of Greece from the drachma to euro in 2002). However, it is true that a plethora of fragments of accounts remain unpublished, and that leaves the fruitfulness of such attempts questionable. Nonetheless, accounts spark scholars’ interest (see the recent volume by Jördens and Yiftach (eds., 2020) on “Accounts and Bookkeeping in the Ancient World”), which is promising for stimulating further research on the topic.